Five Western Journalists in the Doomed City

War damage in the southern section of Nanking. Photo taken by an American missionary, Ernest Forster, on March 17, 1938.

“Wholesale looting, the violation of women, the murder of civilians, the eviction of Chinese from their homes, mass executions of war prisoners and the impressing of able-bodied men turned Nanking into a city of terror,” wrote Frank Tillman Durdin of the New York Times on December 17, 1937, two days after he escaped from the “reign of terror” aboard the U. S. S. Oahu. [18]

Archibald Steele of the Chicago Daily News called the siege and capture of Nanking “Four Days of Hell” in his dispatch on Dec. 15. [19]

C. Yates McDaniel of the Associated Press jotted down the following sentence in his diary on Dec. 16, which was wired to the United States the following day, “My last remembrance of Nanking: Dead Chinese, dead Chinese, dead Chinese.” [20]

Although there were a number of foreign correspondents in the capital of China before the siege, most of them fled Nanking along with ambassadors and other foreign senior officials by Dec. 11.

To this day, the only foreign journalists known to have stayed in the doomed city during the siege and the first few days of Japanese occupation are the three correspondents mentioned above, L. C. Smith of Reuters, and a Paramount newsreel cameraman, Arthur Menken. Consequently they all witnessed the beginning of the carnage.

“Orgy of Burning”: China’s Scorched-Earth Policy

A village outside Nanking in 1936. Forster noted that the village was destroyed by the Chinese military for strategic reasons in December 1937.

“The advance of the Japanese beyond Kuyung was the signal for an orgy of burning by Chinese troops,” described Durdin on China’s military strategy known as the “scorched earth” policy.

The principle behind it was not to leave anything that could be useful to the conquerors. As they beat a retreat from Jurong (Kuyun), about 25 miles (40 kilometers) southeast of Nanking, Chinese troops apparently set torches to not only buildings but also “trees, bamboo groves and underbrush.”

Within the distance of 16 miles (26 kilometers) between Tangshan and Nanking, the New York Times reporter saw whole villages burned to ruins, including barracks, mansions in Mausoleum Park, and numerous other buildings. Durdin estimated the loss caused by “Chinese military incendiarism” at $20,000,000 to $30,000,000. [21]

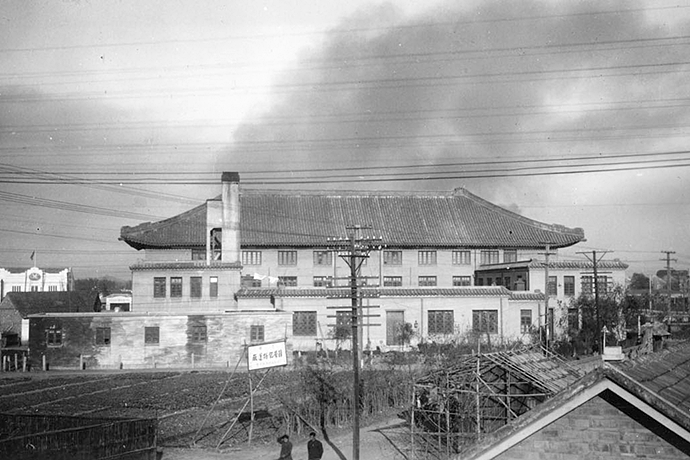

Inside the city wall the Chinese troops continued to set fire to shops and houses. Even the most ornate building in Nanking, the Ministry of Communication, which, according to a correspondent for the Times (London), cost £250,000, was set ablaze.

Though not in Nanking at the time, the Times reporter later interviewed foreign eyewitnesses, who told him that the building was filled with munitions and the explosions caused a “tremendous racket.” [22] McDaniel also recorded the finest edifice in Nanking blowing up and blazing away in his diary on Dec. 12. [23]

City under Projectiles

The U.S. propaganda documentary, the Battle of China, shows how Japanese troops attacked the walled city of Nanking.

Since the beginning of the siege on Dec. 10, Nanking had been caught in the rain of bombs and shrapnel. “From a point of vantage today I watched shell after shell burst into Nanking’s central and southern districts. They came at the average of four a minute,” wrote Steele on Dec. 11. [24]

The same day, as the battle of Nanking was entering a critical phase, the defense commander, General Tang Sheng-chi, declared via the military headquarters in Hankow that Chinese morale was still high and the situation favored their side. According to the Chicago Daily News on Dec. 11 (no byline), he also insisted that he would defend Nanking “to the bitter end.” [25]

But in reality, heavy artillery was brought up and the constant explosions of projectiles shook the ancient city day and night. McDaniel reported to have seen the Purple Mountain being “sprayed by shrapnel” on Dec. 12, [26] one day before the city fell into the hands of the Japanese troops.

Retreat in Panic

Retreating Chinese troops shed their uniforms, firearms and other supplies. A scene from a Japanese propaganda documentary, Nanking.

As it became definite that the Japanese Army would conquer the city in a matter of time, panic swept through the city.

When Nanking’s defense commander, General Tang Sheng-chi, finally ordered his men to retreat at about 5 o’clock in the evening on Dec. 12, it only threw the military into uproar and created confusion since many troops had already been running away toward Xiaguan (Hsiakwan) riverfront, the northern port suburb, and the only way to escape from the city without encountering the enemy. [27]

By late evening the unorganized retreat became a rout. Frank Tillman Durdin of the New York Times and Archibald Steele of the Chicago Daily News saw many of the Chinese troops loot shops for food and other supplies, cast away their arms and shed their uniforms in the street.

Some of them donned civilian clothes, sometimes by robbing civilians of their garments, and others ran away in their underwear. “Streets became covered with guns, grenades, swords, knapsacks, coats, shoes, and helmets,” wrote Durdin. [28]

However, at Yijiang (Ichang) Men (Gate), the northwest gate of the city leading to the riverfront that foreign correspondents called Hsiakwan Gate in their reports, the 36th Division of the Chinese Army, which had formerly been ordered to stop any retreat, confronted those who tried to go through the tiny openings of the gate.

The streets toward the Yijiang Gate became congested with thousands of retreating Chinese soldiers and civilians. Soon panic followed as the crowd fought to squeeze through the only path to the wharf.

Yijiang Men (Gate) after the fall of the city as filmed in the documentary, Nanking.

To make matters worse, the Chinese Army fired machine guns at the retreating soldiers. Many were killed in this fashion and others fell and plummeted to death while attempting to scale the walls near the gate with makeshift ropes made of clothing.

Those who made it to the Yangtze riverbank were ordained to face another tragedy. There was little or no transport to get them across the river.

Tens of thousands of people fought over scarce vessels, quite a few dove into the cold water of winter and drowned, and many others frantically reentered the city, taking a risk of encountering the Japanese troops who were about to complete the encirclement at the Yijiang Men (Gate). [29]

Once back inside the city walls many soldiers turned themselves into the Safety Zone, the refuge camps organized by the remaining Westerners, so that they would be treated as noncombatants by the Japanese troops.

It turned out, however, to be a futile effort.

Instead of answering an ardent plea for mercy put forward by John Rabe, the chairman of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, [30] the invaders began systematic mopping-up operations the moment they entered the city.

Relentless Search for Stragglers

On December 13, 1937, the Japanese Army completed the encirclement. They opened the Zhongshan (Chungshan) Gate, the eastern pivot of China’s defense, and made a triumphal entry into the city.

“After the complete collapse of Chinese morale and the blind panic which followed, Nanking experienced a distant sense of release when the Japanese entered, feeling that the behavior of the Japanese could not possibly be worse than that of their own defeated army,” wrote Steele. “They were quickly disillusioned.” [31]

Japanese troops intensively searched for stragglers and plain-clothes soldiers. A scene from the film Nanking.

The Japanese soldiers did not show any sign of mercy. What the New York Times reporter called “a tremendous sense of relief” soon transformed into an immense fear of death, rape and robbery. As soon as they entered the city, the Japanese troops began an intensive search for stragglers and ex-soldiers.

“The helpless Chinese troops, disarmed for the most part and ready to surrender, were systematically rounded up and executed,” noted Durdin. [32]

They entered into the refugee camps, assembled any able-bodied men for capricious inspections, and marched off the suspects to execution sites. As most historians indicate today, many of the “suspects” probably had no connection with the Chinese Army.

The streets were littered with bodies including some old men who could never have been harmful. Japanese soldiers frequently shot anyone running in sight on the spot and searched house after house in the course of hunting plainclothes soldiers.

Steele saw scores of those “plainclothes suspects” being shot one by one while “their condemned fellows sat stolidly by, awaiting their turn.” [33]

“This afternoon [I] saw some of the soldiers I helped disarm dragged from houses, shot, and kicked into ditches,” read the diary report of C. Yates McDaniel of the Associated Press on Dec. 15. [34]

Looting in the Entire City and Rape All Over

The Japanese soldiers plundered the entire city and looted anything they pleased in Nanking. “Nearly every building was entered by Japanese soldiers, often under the eyes of their officers, and the men took whatever they wanted,” reported Durdin. [35]

“I saw Chinese troops looting shop windows, but later I saw the Japanese troops outdo them in a campaign of pillage which the Japanese carried out not only in the shops but in homes, hospitals and refugee camps,” wrote Steel. [36]

McDaniel saw one soldier collecting some $3,000 by threatening poor civilians in the Safety Zone with a bayonet. [37]

They robbed Chinese houses and shops, ripped off refugees and occasionally broke into the foreign properties. The Times (London) reported that the Japanese soldiers paid a visit to the American-operated University Hospital and “robbed the nurses of their wrist watches, fountain pens, flashlights, ransacked the buildings and property, and took the motor-cars, ripping the American flags off them.” [38]

A woman being carried into the hospital for gunshot wounds inflicted by a Japanese soldier who threatened to rape her. Photo taken by Forster.

According to the diaries and letters of remaining Westerners, their houses were also sporadically invaded.

Many Chinese women were molested freely and violently. However, because the five foreign journalists fled Nanking within three or four days after the collapse of the city, they could not possibly grasp the extent of rape cases. Compared to the relentless executions and looting by the Japanese troops reported in their articles, rape cases were mentioned rather briefly.

It was the Western members of the Nanking Safety Zone who first revealed the countless rape cases committed by the Imperial Army soldiers to the world.

Many years later, long after the war ended in 1945, a number of Japanese journalists (see Reign of Terror) and former soldiers (see Confessions) also came forward to speak up about what they had seen or what they had done in Nanking.

As urged by Japanese authorities, Durdin, Steele, Smith and Menken were evacuated to Shanghai on Dec. 15th aboard the gunboat Oahu, on which they had telegraphed their first reports on the Nanking Atrocities. [39] McDaniel stayed a day longer and headed for Shanghai on the Japanese destroyer, Tsuga. [40]

Go back to: Table of Contents

[References]

- Tillman Durdin, “All Captives Slain,” the New York Times, 18 December 1937.

- A. T. Steele, “Nanking Massacre Story: Japanese Troops Kill Thousands,” Chicago Daily News, Red Streak Edition, 15 December 1937.

- C. Yates McDaniel, “Nanking Horror Described in Diary of War Reporter,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 18 December 1937.

- Durdin, “Japanese Atrocities Marked Fall of Nanking After Chinese Command Fled,” the New York Times, 9 January 1938.

- “Terror in Nanking,” the Times (London), 18 Dec. 1937.

- McDaniel.

- Steele, “Big Guns Rake Nanking, Defense Is Abandoned,” Chicago Daily News, 13 December 1937.

- “Retreat Course Changed,” Chicago Daily News, 11 December 1937.

- McDaniel.

- Kasahara, Nanking Jiken [The Nanjing Incident], 128-133.

- Durdin, “All Captives Slain” and “Japanese Atrocities Marked Fall of Nanking After Chinese Command Fled”. See also Steele, “War’s Death Drama Pictured by Reporter,” Chicago Daily News, 17 December 1937.

- Kasahara, Nanking Jiken [The Nanjing Incident], 128-133.

- A series of the official documents written by the members of the International Committee to the Japanese authority were collected in Documents of the Nanking Safety Zone, ed. Hsü Shushi (Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh, 1939). The whole book is reprinted in Documents of the Rape of Nanking, ed. Timothy Brook (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999).

- Steele, “Nanking Massacre Story.”

- Durdin, “Japanese Atrocities Marked Fall of Nanking After Chinese Command Fled.”

- Steele, “War’s Death Drama Pictured by Reporter.”

- McDaniel.

- Durdin, “All Captives Slain.”

- Steele, “War’s Death Drama Pictured by Reporter.”

- McDaniel.

- “Terror in Nanking,” the Times (London).

- Hata, Nanking Jiken [The Nanjing Massacre], 2-3.

- McDaniel.

©2000 Masato Kajimoto. All Rights Reserved.